Materialism

a sculpture on reversed engineering

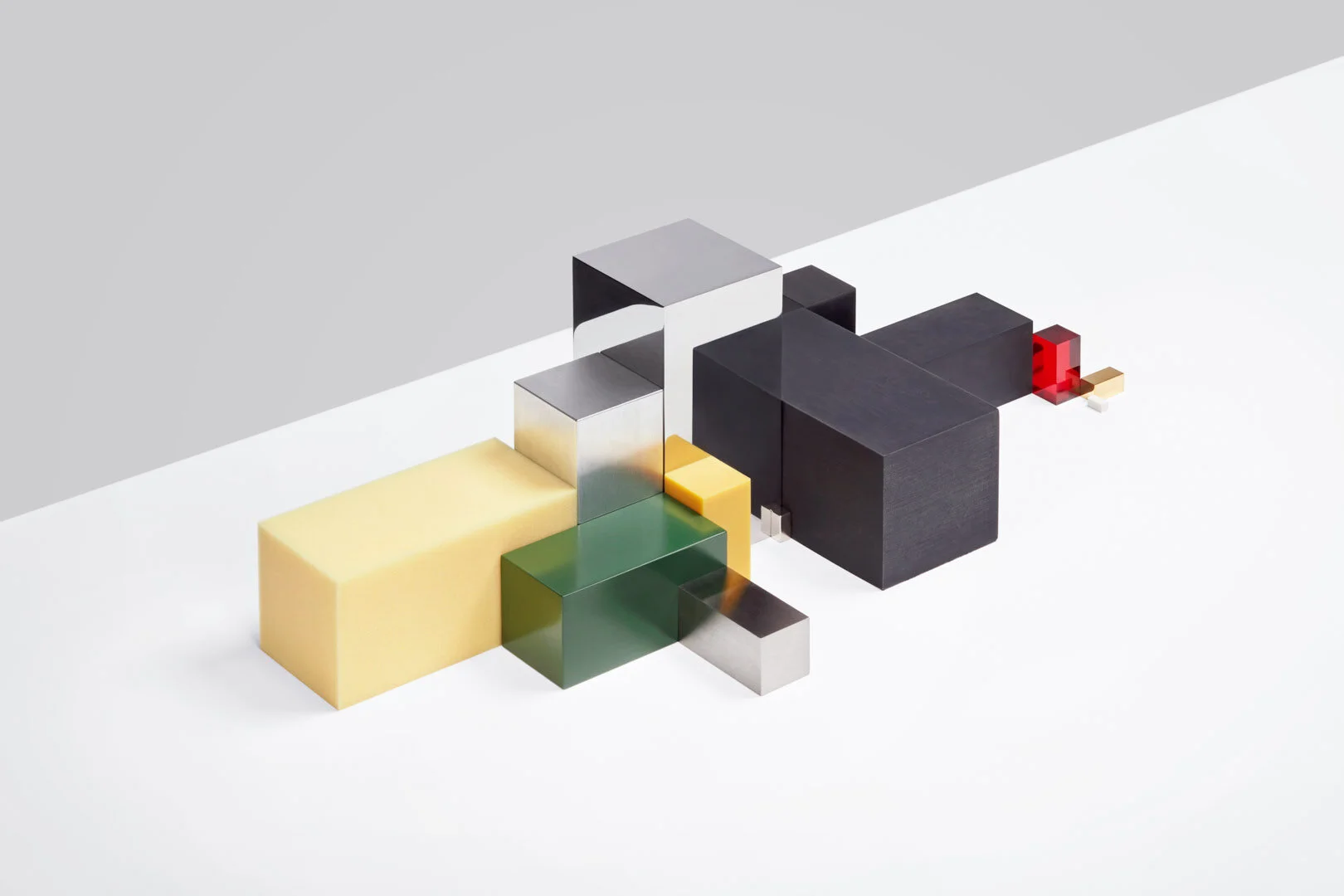

Materialism confronts the viewer on a very elementary level with the things we surround ourselves with and the materials that comprise them. The work calls for contemplation on how people deal with the raw materials at their disposal.Everyday products such as a vacuum cleaner, Volkswagen Beetle, pencil, or PET bottles, have been reduced to the exact quantity of the specific raw materials from which they are made, shown in the form of rectangular blocks.

Gazelle Bike from 2005 - work 2019

VW Beetle from 1980 - work 2018

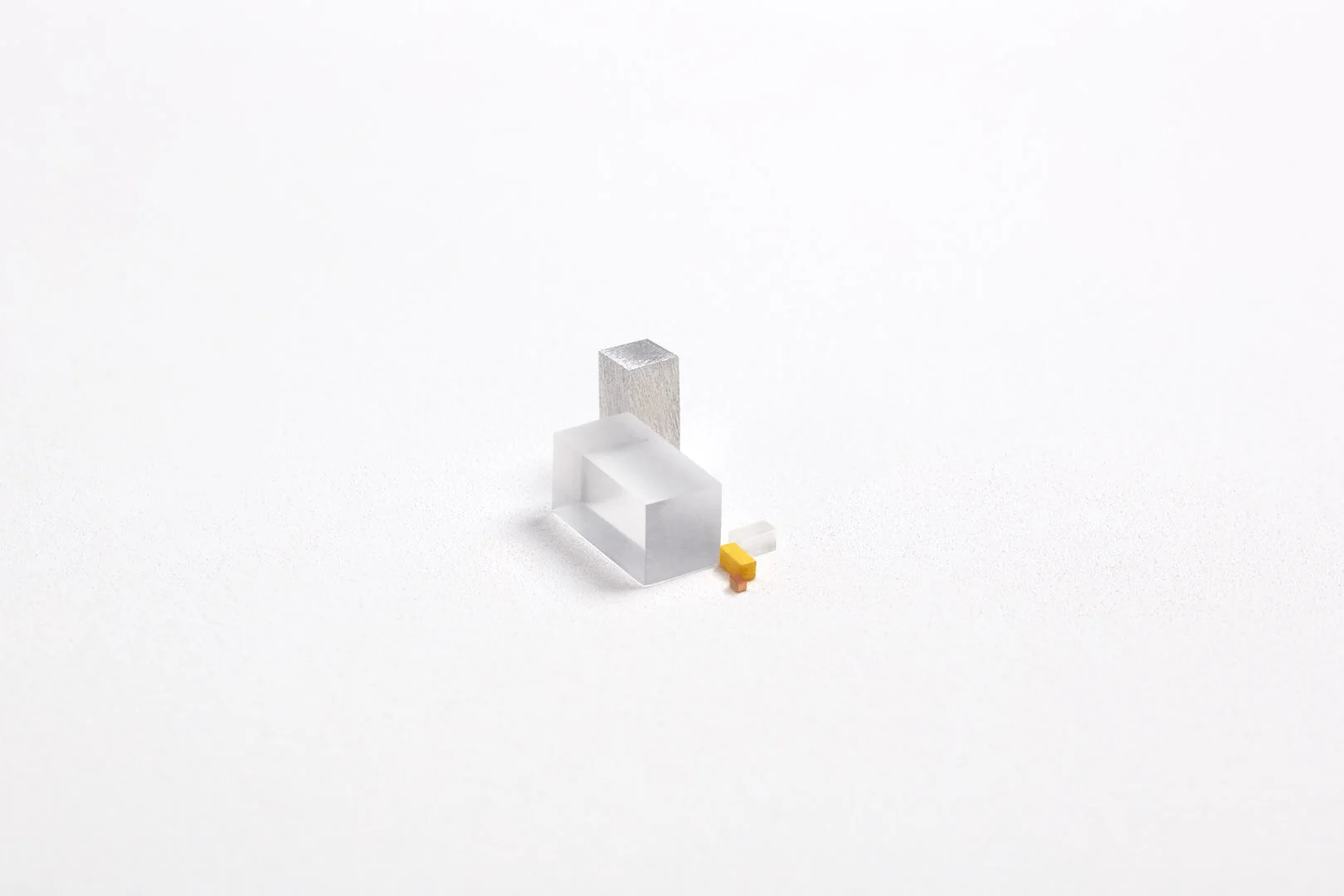

Lightbulb 2018

LED 2018

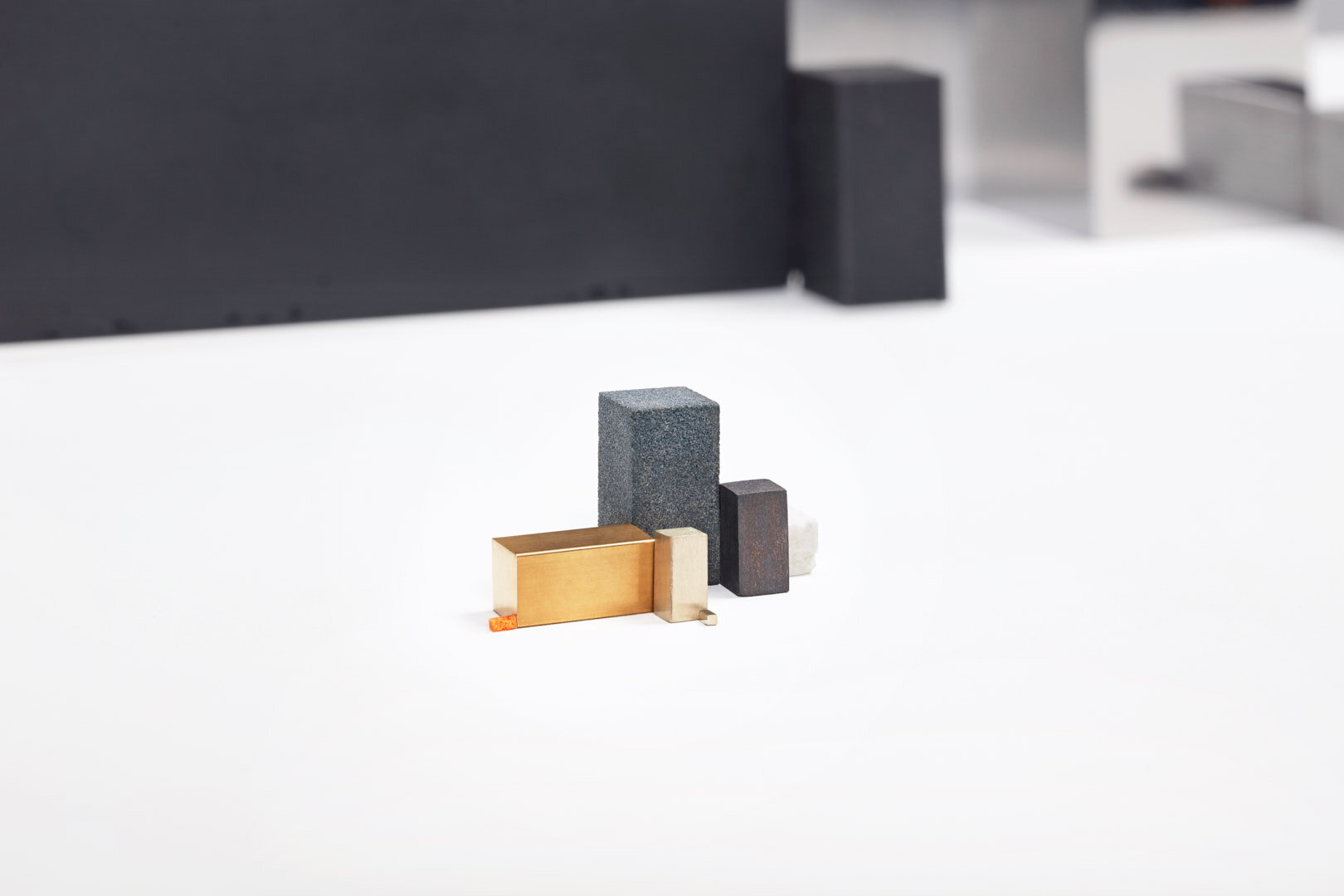

Russian machine gun AK-47 with bullet during Vietnam war 1975 - Work 2019

American machine gun M-16 with bullet during Vietnam war 1975 - Work 2019

Close up M-16 bullet during Vietnam war 1975 - Work 2019

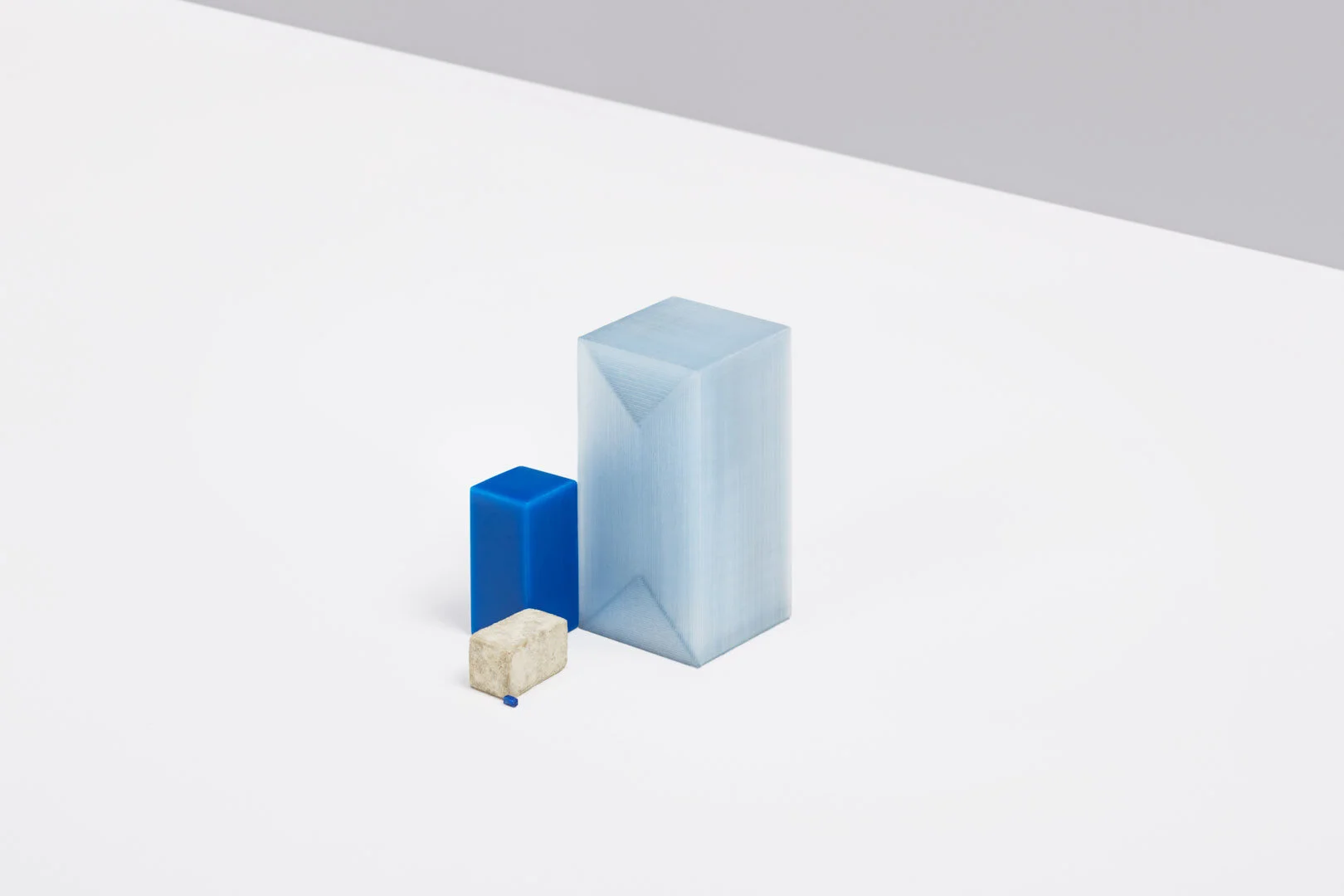

I-phone 4 from 2010 - work 2019

Nokia 3210 from 1999 - Work 2019

Spa water bottle 2018

Materialism is an ongoing research project in which the artists explore the everyday “made objects” that surround people.

Since the Renaissance, scientists have probed the world systematically, using reason and observation to unveil the mysteries of nature, to understand its materiality, and begin to question humanity’s relationship to it. That process, which began centuries ago, has yielded immense knowledge but also the realisation that it is all but a drop in the ocean of what is knowable. During the same time, civilisation has introduced millions of new ‘artificial species’ through industrialisation and ecosystems of commerce, objects that support our pleasant contemporary existence and contain myriad materials forged together by design. Yet nowadays, people feel disconnected from this materiality, blind to the inner workings and composition of all these artificial things.

For Materialism, the artists ‘de-produce’ the produced, deconstructing familiar things about which we tend only to consider their function. DRIFT makes clear how much of the matter within these objects is extracted from the earth. In the process, they reverse the mandates of engineering required for mass production which are standardisation, modularisation, and abstraction. Nauta and Gordijn essentially create uniqueness, unity, and ‘de-abstraction’ in the form of simple geometric blocks. These blocks of varied, pure colour make visual rhymes with the earliest works of Abstract art such as paintings of Kazimir Malevich, Hilma af Klint, and Piet Mondrian. And, although the goal of ‘de-abstraction’ may sound opposed to the work of these 20th century artists, the purpose of their work and of Materialism is aligned: to make the essential nature of the world visible.

In one example, DRIFT completely dissected a Volkswagen Beetle, to the level of the smallest component, then organised all of these by their material and measured each group’s accumulated mass. These masses are represented in 42 pure material volumes that begin to tell a variety of stories. The automobile, from 1980, contained surprising amounts of horsehair, cotton, and cork, amongst other unexpected commodities. These relate a tale about availability, tradition, and the state of our technical and material knowledge almost four decades ago.

Control over raw materials is still at the heart of numerous geopolitical tensions and, while people might like to think of these as a matter for politicians, everyone is implicated. Everything that is bought and consumed has an impact, reinforcing complex systems of resource extraction, labor, manufacturing, and distribution. Materialism works to reveal the dimensions of the materialism these systems feed, illuminating the excessive use of the earth’s gifts, irreplaceable matter that humans incessantly rip away from it, squander, and then dispose of with little thought. Understood this way, in pursuit of the most basic things, like a pencil or a plastic water bottle, people are collectively acting as a deviant child stealing from his mother.

For Materialism, the artists also took apart and created volume sculptures of other objects, such as a light bulb, bicycle, vacuum cleaner, and a plastic bag from a local supermarket. One of the most startling discoveries in the course of the hands-on research was the significant amount of plastic and copper that is used for a single meter of electrical cable, an utterly ubiquitous product. This leads DRIFT to imagine vividly how many hundreds of meters of cable can be found in the studio, in its home city of Amsterdam, and in the world. The billions of kilos of copper and plastic, if represented by Materialism, would make blocks that would soar upwards past the clouds. If humankind could somehow perceive this connection to materials, to the collective consumption and the earth it impoverishes, it would be a leap in our social evolution, in building an awareness that everyone must somehow become better stewards of the future.